Public Healthcare Crisis in Venezuela

By Valerie Bittleston

Published Summer 2020

Special thanks to Kaytee Johnson for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

The public healthcare crisis in Venezuela has been compared to the emergency status primarily declared on countries at war. Lack of investment in their free public healthcare system has depleted the country of medical personnel, infrastructure, and supplies. Limited to no access to essential medicines and healthcare services have increased the spread of infectious diseases. Venezuelans often migrate in order to seek aid elsewhere, carrying previously eradicated diseases with them. Mother and infant health is of utmost concern as mortality rates are increasing at exorbitant rates with no end in site. The government implemented a public healthcare program in 2003 to improve healthcare, but it had limited success, and international aid and internal NGOs can only do so much to ease the effects of the crisis.

+ Key Takeaways

- The lack of investment and government spending allocated to healthcare annually has significantly dropped in recent years and is heavily tied to the healthcare crisis in Venezuela.

- Venezuela is experiencing an extreme shortage in medicine, supplies, and equipment that is necessary to prevent, diagnose, and treat health conditions.

- Thousands of doctors and nurses from Venezuela have migrated due to low wages, inadequate supplies, and government corruption—leaving hospitals and clinics severely understaffed.

- Measles, diphtheria, and malaria vaccinations have fallen below the essential immunization levels in Venezuela due to the healthcare crisis, which is shown to lead to increased diffusion of these diseases.

- Maternal mortality in Venezuela increased by 65% between 2015 and 2016, and infant mortality increased by 30%.

- Government interventions are the most likely practices to succeed in improving public healthcare in a socialist country like Venezuela; however, there are other practices assisting in easing the suffering from the crisis.

+ Key Terms

GDP—“The gross national product, excluding the value of net income earned abroad.”1

Inflation—“A continuing rise in the general price level, usually attributed to an increase in the volume of money and credit relative to available goods and services.”2

Hugo Chávez—The president of Venezuela from 1999 to 2013. He was the leader of a socialist political revolution in which he reformed many social programs, including the Barrio Adentro program.3

Fidel Castro—A political leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008 who “transformed his country into the first communist state in the Western Hemisphere.”4

Nicolás Maduro—The president of Venezuela since the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013. He is a “zealous proponent of chavismo (the political system and ideology established by Chávez).”5

Bolívar fuerte—The current monetary unit of Venezuela. Formerly bolívar and bolivar. Each bolívar fuerte is divided into 100 céntimos (cents). The bolívar fuerte (the equivalent of 1,000 bolivares) was introduced in 2008 in an attempt to curb high inflation and simplify financial transactions. It replaced the bolívar, which had been adopted as Venezuela’s monetary unit in 1879.6

Bolivar soberano—A currency introduced in 2018 by Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro. It is worth 100,000 bolivares fuertes.7

Barrio Adentro—A social health reform program initiated in 2003 by Hugo Chávez, with an aim to bring healthcare to the slums and rural neighborhoods in Venezuela.8

Malaria—“A human disease that is caused by sporozoan parasites in the red blood cells, is transmitted by the bite of anopheline mosquitoes, and is characterized by periodic attacks of chills and fever.”9

Measles—“An acute contagious disease that is caused by a morbillivirus and is marked by an eruption of distinct red circular spots.”10

Diphtheria—“An acute febrile contagious disease typically marked by the formation of a false membrane especially in the throat and caused by a gram-positive bacterium that produces a toxin causing inflammation of the heart and nervous system.”11

Hypertension—“Abnormally high blood pressure and especially arterial blood pressure.” High blood pressure often occurs when the arteries or veins become blocked or narrowed, making the heart work harder to pump blood. Hypertension is serious, as it can lead to heart attacks and strokes.12

WHO List of Essential Medicines—Find their list here: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325771/WHO-MVP-EMP-IAU-2019.06-eng.pdf?ua=1.

Context

The Latin American country of Venezuela has suffered economic collapse and government corruption that has led to the state of crisis in its public healthcare system today. Nationwide, Venezuelan citizens are unable to receive the care they are promised by their socialist government. Socialized medicine, often referred to as universal healthcare, is run and paid for by the Venezuelan government, though private healthcare is also available.13 This brief will focus on the crisis within the country’s system of free public healthcare, although there are some who choose to pay for privatized healthcare.14 The percentage of the population that relies solely on public healthcare is unclear, but it seems to be a significant majority.

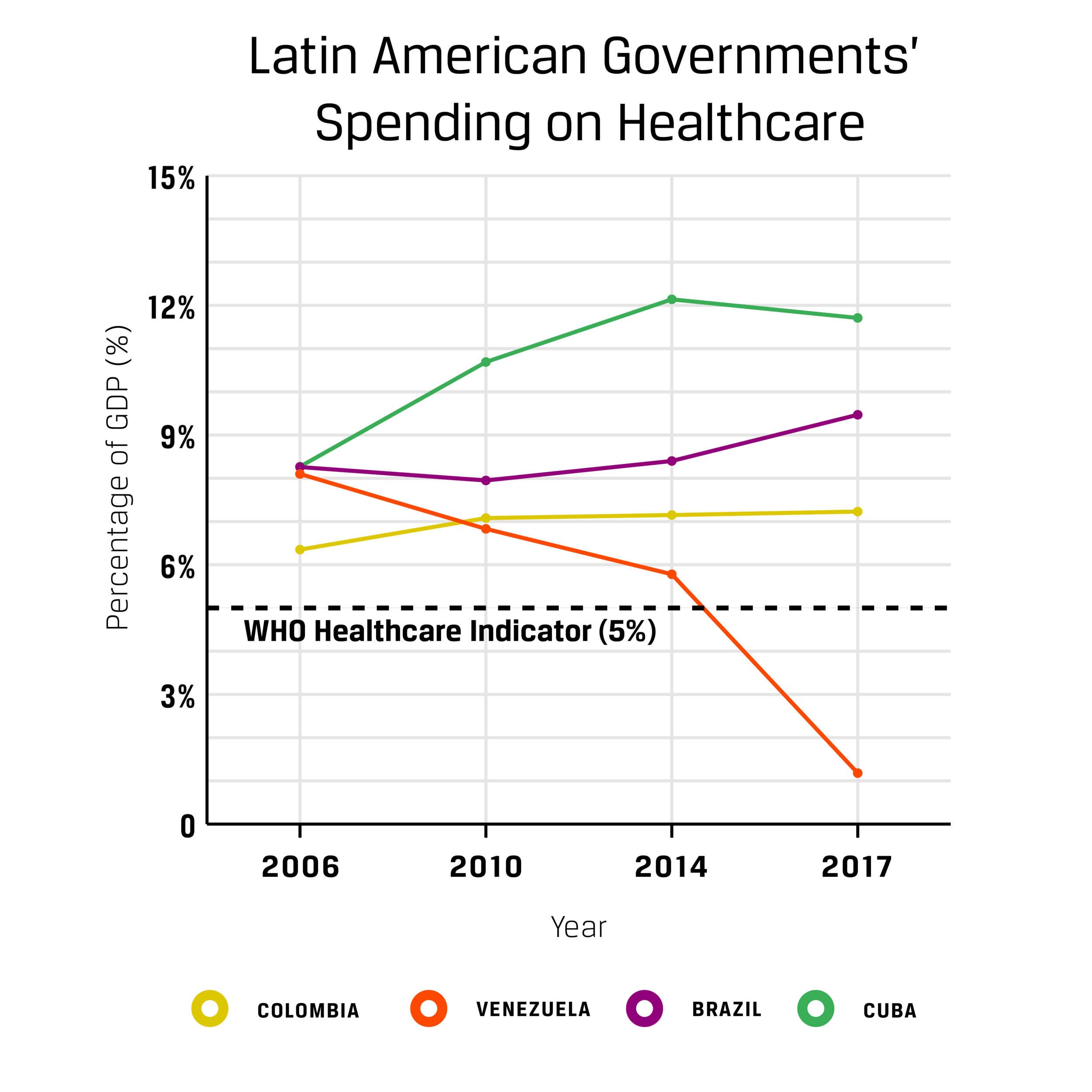

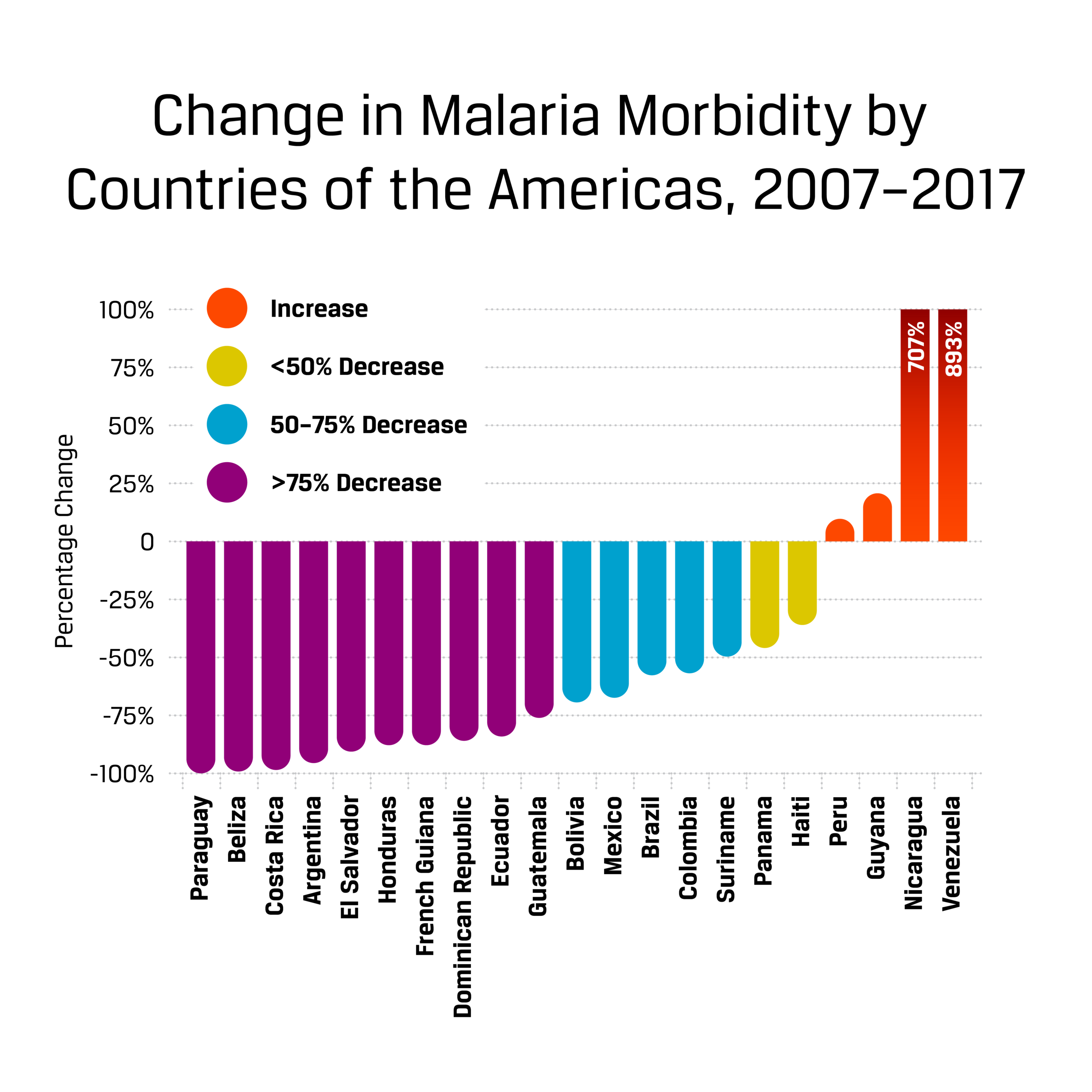

Public healthcare in Venezuela was once praised internationally,15 particularly during the mid-1900s when the country led the fight to eradicate malaria and had admirable vector control and public health policies, but more recent data from the past several decades shows evidence of the inadequacies within the public healthcare system and warn of an ever-increasing crisis.16 Ninety-eight percent of Venezuelan physicians that were surveyed in 2018 felt that the healthcare crisis was the worst it had been in 30 years.17 Many common indicators of the success, or failure, of healthcare such as mortality rates and spread of infectious disease also indicate a level of crisis. In 2008, Venezuela only had 106 cases of malaria, but by 2018 confirmed cases rose to 1.3 million, with an expected increase moving forward.18 In 2016, maternal mortality rates went up by 65%, and infant mortality rates increased by 30%19 nearly every other country is currently seeing decreases in these rates.20 A United Nations (UN) publication states that “a country’s difficult financial situation does NOT absolve it from having to take action to realize the right to health.”21 Although Venezuelan healthcare has had a history of issues, since the height of the government healthcare program in 2006, healthcare spending has dropped significantly from 8.1% of gross domestic product (GDP) to less than 1.18% in 2017.22 The World Health Organization (WHO) uses healthcare funding of at least 5% of the country’s GDP as an indicator of adequate healthcare.23 Additionally, some studies suggest that increasing a country’s current spending by 10% will increase life expectancy and decrease infant mortality.24 This drop in spending shows that Venezuela is in clear violation of the previous UN directives.

Government spending on healthcare is proportional to the success of a public healthcare system. At the turn of the century, in an attempt to become reelected as president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez began to reform social programs, one of which was the Barrio Adentro program—the government’s system of providing free public healthcare and healthcare facilities.25 In 2002, Chávez and Cuban president Fidel Castro initiated a deal, exchanging oil for labor, a deal that is still in place to this day.26 Over time Cuba would be sending 30,000 medical professionals to Venezuela, and Venezuela would designate 53,000 barrels of oil a day to Cuba, though it increased to 90,000 by 2005, with reduced financing.27 Cuba has a highly educated population in terms of healthcare, and most doctors seek work abroad because they will be able to earn a higher income than if they remain in Cuba.28 At its height, there were 30,000 Cuban medical professionals supporting the program and implementing a Cuban-style healthcare system.29 The Barrio Adentro facilities were fairly successful in the early 2000s, bringing free public healthcare to the impoverished areas of Venezuela.30 Then, due to lack of continued government investments in the future of the oil industry—namely, the monopolistic state-owned company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), which was the primary funder for Barrio Adentro—the majority of facilities were closed or abandoned.31

Since the economic crash in 2014, inflation has severely affected the already diminishing Venezuelan healthcare system.32 Oil represents 95% of the country’s exports, thus Venezuela is dependent on the oil industry for overall GDP.33 When the value of oil quickly dropped in 2014,34 the effects rippled across the country, taking a toll on social programs such as Barrio Adentro. Inflation, which is measured as a comparison between the former Venezuelan currency bolivar fuerte and the US dollar, hit a record high at a 10 million percent inflation rate in 2019.35 In 2018, the inflation rate became so high that Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro introduced a new currency, the bolivar soberano, to combat inflation.36 That same year, accounting for inflation, the minimum wage was 40,000 bolivares, an equivalent of $2 a month, which is not even sufficient to buy a carton of eggs.37 For further context, a study has shown that for a breadwinner in Venezuela to feed their family, they should earn US $146.41 a month, at a minimum.38 Venezuelans are living with the reality that they have far less than the bare minimum needed to survive—a situation that is cause for concern and very relevant to the country’s healthcare struggles.

Healthcare statistics have been hidden from the public eye and falsified by the Venezuelan government. In May 2017, the Venezuelan Health Minister was fired after publishing health data that had been withheld from the public for two years.39 That same year, the government claimed that the Barrio Adentro facilities completed over 118 million consultations that year, but a 2017 poll reported that only 200,000 people used their services. In order for those numbers to match, each of those beneficiaries would have had to receive consultations 600 times in one year.40 Unclear and potentially falsified reporting makes it difficult to have precise and accurate data concerning the healthcare crisis in Venezuela. Lack of transparency masks the reality that Venezuela is in a fast descent towards a state of humanitarian and refugee emergency that is generally only declared in war-torn countries such as Syria and South Sudan.41 Unlike these two countries, Venezuela has received very little international funding for humanitarian aid.42 The severe state of crisis in Venezuela is masked by false or inadequate reporting. All of these factors contribute to the reality that—due to a lack of accurate data collection—this brief will, in places, illustrate issues using some older data, comparison data, or even occurrences reported by news outlets.

Contributing Factors

Economic Barriers

Economic failures within the government have been a major factor in the healthcare system reaching its current state of crisis. When Mission Barrio Adentro was first introduced, PDVSA invested $126.5 million to support the program. In 2015, the PDVSA increased its contributions to social programs by 72%.43 Though this appears to be beneficial, the large amount of government funding into the program has caused healthcare to be too dependent on a volatile oil economy for its success. As previously mentioned, Venezuela spent 8.1% of its GDP on healthcare in 2006, but they were spending only 1.18% of their GDP on healthcare by 2017.44 Since 2006, the percentage of government spending allocated to healthcare has clearly dropped. Because of extreme inflation, this drop in percentage spent is even more significant than it appears because the bolivar is worth less than it was before. The healthcare crisis is heavily tied to this lack of investment and government spending allocated to healthcare annually.45

In addition to national economic insecurity, the economic position of Venezuelan individuals themselves further contributes to their struggle to access healthcare. The government has attempted to combat the economic crisis, but healthcare costs continue to be inflated and primarily paid for by individuals—even in a system that is meant to be public and free.46 To combat the severity of the crisis and enable individuals to pay for their healthcare, the government issued monthly bonus checks to approximitely 10 million Venezuelans in 2019. These checks often amounted to less than US $5, but the funding more than doubled many household incomes, according to reports.47 Unfortunately, US $5 is equivalent to 100,000 bolivares and can buy a Venezuelan only 4 pounds of laundry detergent.48 Since 2019, the worst year for Venezuela’s economy, the government has resorted to increasing the minimum wage, which has lowered inflation but has yet to influence the pricing and accessibility of healthcare. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in 2017 was at 62.99% in Venezuela, well above Latin America and the Caribbean’s average of 28% and the worldwide average of 18% that year.49 For a healthcare system that is supposed to be free for the public, these percentages are especially alarming. While there is not a complete breakdown of what Venezuelans’ out-of-pocket-expenditure goes toward, the majority of this cost is for private healthcare due to the inadequacy of the public healthcare system.50 The crisis within the healthcare system is heavily influenced by the government choosing to not properly fund their own free public healthcare system, thus individuals are left with expenses they cannot afford.

Lack of Supplies

Venezuela is experiencing an extreme shortage in medicine, supplies, and equipment that is necessary to prevent, diagnose, and treat health conditions.51 The government has inadequately provided for the supply needs of the free public healthcare system and restricted international aid from providing assistance.52 On multiple occasions, Nicolás Maduro has refused international aid, including much needed medical supplies. In May of 2016, Maduro asked the Venezuelan Supreme Court to block a law that would increase the amount of humanitarian aid entering the country.53 Then, in early 2019, Maduro refused shipments of medical supplies from the United States that were waiting on the Colombia-Venezuelan border, stating that his people weren’t beggars. He then released propaganda framing foreign aid workers as enemies and rapists.54

Refusing much needed international aid is exacerbated by the government’s failure to provide the free public healthcare they promote. The president of the Venezuelan Association of Medical Equipment estimated that $1 billion is the minimum cost to cover all necessary medical imports into Venezuela for a year, but in 2014 the government barely supplied $200 million.55 This correlates to the decreased importing of medicine by 70% between 2012 and 2016.56 The lack of investment in healthcare supplies and decreased imports contribute to the severity of the shortages felt across the country in the healthcare community.

Shortages of medical supplies make accessibility to healthcare in emergency and preventative situations an ever increasing issue. In the public health sphere, hospitals have up to 95% shortages on medicine, and pharmacies are close behind with 85% shortages, meaning that Venezuelans are only able to acquire 5%–15% of their needed medications through the healthcare system.57 These medication shortages can be seen through reports of patients admitted for surgery who are asked to provide their own needles and antibiotics due to the fact that hospitals do not have the proper supplies.58 Human Rights Watch (HRW) says most Venezuelan hospitals have few to none of the medicines on the WHO list of essential medicines—this list includes very basic medications like antibiotics, sedatives, cancer treatment and pain killers.59 An August 2016 poll of 200 Venezuelan doctors reported that 76% of the public hospitals they worked in lacked the basic medicines that doctors would need to run a functioning hospital.60 One anecdote reported by NBC illustrates the effect of lack of supplies in Venezuelan healthcare: a young girl from Caracas scraped her knee and it became infected due to unclean water, causing inflammation and a severe fever. She was taken to the hospital and the knee was drained with a previously used needle. Days later the infection spread to her heart because the hospital lacked the necessary medicine to prevent it. She was able to be treated and recover, due to the death of another child her age and the opportunity to use his surplus medication.61

A survey of just 40 Venezuelan hospitals revealed that between November 2018 and February 2019, 1,557 patients died because the hospitals did not have the supplies necessary to treat them.62 Additionally, the UN stated in 2019 that 300,000 Venezuelans’ lives were at risk because they had been waiting for over a year to receive needed medicines.63 Additional reports claim that many psychiatric hospitals in Venezuela have patients who cannot function without medication and sedatives attack nurses and other patients when they are deprived of those necessary supplies due to shortages.64 The healthcare system suffers from severe shortages of supplies that put both doctors and patients at risk and further perpetuates the healthcare crisis nationwide.

Inadequate Infrastructure

Deficient Healthcare Facilities

Accessibility of Barrio Adentro clinics has significantly decreased, making it difficult to obtain quality healthcare. When the Barrio Adentro missions were first announced in 2002, the goal was to have 600 comprehensive medical diagnostic centers that would cover every municipality in Venezuela.65 The government planned to build clinics in every neighborhood to cover about 250 to 350 families each, making healthcare more accessible to rural Venezuelans.66 By 2017, however, it was reported that 80% of the 13,496 neighborhood and comprehensive centers that had previously been built were closed.67 While official reports have not been released, anecdotes suggest that centers are closed by the government for reasons such as pending renovations that are never completed or a lack of supplies.68 If 80% of these clinics are closed, that means that a clinic that normally covers 300 families would be covering 1,500. This equates to an average of 6,000 people per clinic, which is usually run by one doctor and often only has one or two rooms.69 The clinics that are open are unclean and inadequately staffed and stocked, thus providing little benefit to the people they are supposed to serve and posing a heightened risk during major pandemics or disease outbreaks like COVID-19.70

Poor Sanitary Conditions

Hospitals also lack consistent running water to provide sanitary environments for medical practices. In a 2019 national poll in Venezuela, intermittent water availability was reported by 70% of hospitals, and an additional 20% of hospitals reported they had little to no water.71 Jugs and bottles are often filled from dripping taps to provide the water for all necessary functions.72 Surgeries are scheduled around water availability, and anecdotal evidence suggests that water pots are carried around by medical staff to clean hands, bathrooms, and surgical tools.73 In a physician poll taken in 2018, 72% of physicians strongly agreed with the assertion that working conditions in public hospitals were in violation of basic ethics and human rights.74 In 2010, the UN General Assembly declared clean water and sanitation to be a human right because it is a foundation to providing other basic rights.

Low Hospital Bed Availability

Available hospital beds, a common measure of healthcare success worldwide, are far below recommended or even acceptable rates in Venezuela. In government-supplied public hospitals, doctors are reportedly only able to use 16,300 of the 45,000 hospital beds available.75 This is primarily due to a lack of supplies and medical personnel to staff these beds as well as lack of funding to provide care for more patients. In a nation of 30 million people where it is estimated there should be 100,000 beds available, the number of available beds in Venezuela falls below 25,000, including beds in private clinics.76 For patients who need to be admitted to a hospital's intensive care unit (ICU), it is even more difficult to find an open bed, with reports claiming there are only 84 available ICU beds in the entire country.77

Inadequate Emergency Supply and Preparedness

Lack of accessibility to adequate healthcare is exacerbated by the frequent blackouts that plague the country. These nationwide power outages are due to a failure to invest in maintenance for the Venezuelan national dam that is meant to provide electricity and power to the majority of the country.78 Modern healthcare is dependent on electricity for testing, treatment, and life support. Between November 2018 and February 2019, it was reported that 79 patients in 40 hospitals across Venezuela died due to power outages.79 Lack of emergency supplies and generators in hospitals make it very difficult to provide essential care, especially to patients in critical condition. In March 2019 alone, hospitals lacked electricity for as much as 507 hours, or two-thirds of the month, with shortages lasting as long as a week.80,81 In 2018 a national hospital survey reported that 68% of Venezuelan hospitals experienced failures in their electricity supply.82 This was previous to early 2019 when blackouts became more frequent and extended, but it illustrates the lack of attention given to healthcare, especially the needs of medical personnel to provide even basic care for their patients.

Medical Personnel

Shortage of Medical Professionals

In 2014, 39,900 medical personnel were registered with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), but between 2012 and 2017, 22,000 physicians left Venezuela and the healthcare system was left depleted.83 The Venezuelan government has been using Cuban doctors to achieve their goal of having a doctor for every neighborhood, but according to Venezuelan law, these doctors are practicing illegally. In order for a foreign doctor to practice medicine in Venezuela, they must have a degree from a Venezuelan university or pass an examination.84 Since 1999, when Chávez first traded oil for Cuban doctors, 31,000 doctors have traveled to Venezuela to help support the Barrio Adentro missions.85 Cuban doctors were brought over to make up the difference of doctors needed to sustain the Barrio Adentro missions, with the plan to replace them with Venezuelan doctors over time. In 2007, medical schools were training 17,000 Venezuelans to become doctors.86 Unfortunately, due to low wages and inadequate working conditions, many native Venezuelan doctors and other medical professionals have fled the country for other, more fruitful ventures. In 2016, 88% of medical students in the graduating classes of four major Venezuelan universities planned to leave the country after graduation.87

Wages in 2019 were less than US $10 a month for medical specialists and surgeons, and usually around US $4–$5 for regular physicians and nurses.88 Such low incomes cannot convince doctors to stay in Venezuela. Venezuelan medical personnel experience many unfavorable conditions such as threats from patients’ families when the doctors are unable to adequately treat them due to a lack of supplies.89 These negative experiences could contribute to many doctors pursuing work outside of the country. Doctors and nurses also have trouble getting to work, with the military restricting how much gas people are allowed to buy, keeping medical personnel from attending to the needs of their patients and providing essential healthcare.90

Unethical Practices of Medical Personnel

Corrupt government involvement in healthcare restricts the quality of healthcare that medical personnel can provide their patients. Though Maduro’s healthcare program appears to have well-meaning goals, those goals are not coming to fruition due to inadequate program implementation. For example, anecdotal evidence provided in 2019 shares the experience of 16 Cuban medical professionals who were restricted from providing medical assistance unless a patient voted for and supported Maduro.91 Additionally, part of the Barrio Adentro program was to do home visits, but these came with a political aim rather than with the intent to provide preventative care to 100% of Venezuelans, as the program promised. While it was not a part of Maduro’s publicized plan, anecdotes suggest that a vote was often required in exchange for medical treatment or supplies.92 Doctors would go into homes with deliveries of vitamins and Venezuelans were usually willing to vote for Maduro in return, if required.93 Another hidden portion of Maduro’s deal with Cuba required Cuban doctors to save a life every day; one doctor reported this requirement sometimes meant putting a healthy patient on an IV drip so that the daily quota could be achieved.94 In a country suffering from lack of supplies and necessary infrastructure, doctors have to adhere to standards that are not necessarily focused on the well-being of patients and medical personnel, further contributing to the inadequacy of the public healthcare system.

Consequences

Prevalence of Disease

The healthcare crisis has led to an increase of infectious diseases. Without treatment, infectious diseases are concerning because individuals are highly contagious and outbreaks are more likely to occur. This has proven to be true in Venezuela. Urban populations are at higher risk of contracting diseases because they are more likely to be exposed due to a higher population density.95 Given that a larger percentage of Venezuela's population lives in urban areas (88.21%) than in rural areas (11.79%),96 this poses a significant risk to a large portion of the population.

Measles, diphtheria, and malaria vaccinations have fallen below the essential immunization levels in Venezuela due to the healthcare crisis, which is shown to lead to increased diffusion of disease.97 Within a decade, immunization percentages have dropped significantly as access to quality healthcare has declined. In 2008, the country reported 93% immunization for measles among children ages 18–24 months, but by 2018 the percentage fell to 74%.98 Studies have shown that immunization rates for a population need to be 90–95% in order to avoid an outbreak of the measles.99 Venezuela’s low immunization rate puts the population in danger because there is a high risk of being exposed to infectious diseases, causing the vaccination to have no effect on those who do receive it. As expected, measles returned to Venezuela in 2017; in 2018 alone there were 2,154 cases confirmed.100 Additionally, Venezuela’s immunization program began failing in 2010, and since then approximately 40% of the population remains without all four doses of the diphtheria vaccination.101 Diphtheria outbreaks beginning in 2016 have spread to 22 of the 23 states in Venezuela, with cases in 2018 rising to 1,086.102 In 2018, over one million cases of malaria were reported despite the disease being eradicated in Venezuela back in the 1940s.103 Severe shortages in antimalarial drugs and treatment in Venezuela are making it increasingly difficult to overcome this significant rise in malaria cases.104

In addition to malaria, measles, and diphtheria outbreaks caused by low vaccination rates, many other common and treatable health issues claim a number of Venezuelan lives due to insufficient healthcare. The leading cause of death is heart disease, accounting for about 20% of deaths a year in Venezuela.105 Venezuela has long struggled with cardiovascular disease, but the numbers continue to increase with no treatment to curtail the downward spiral. The majority of deaths due to cardiovascular disease are connected to hypertension, which is a common ailment that affects many Venezuelans.106 In a survey of 7,424 Venezuelans with a history of hypertension, 41.2% did not have their hypertension under control and 54.3% were unaware they had the condition.107 For patients to have the best possible outcomes, healthcare workers should provide necessary medication as well as adequate explanation of the disease. Additionally, diarrhea has increased by 34.6% and acute bronchitis by 40% between 2014–2016,108 showing that decreased healthcare impacts even common health issues in Venezuela.

Migration

The healthcare crisis has caused many Venezuelans, not just doctors, to flee the country to acquire healthcare elsewhere, especially across the border to Colombia. Colombian migrant officials reported that of the 50,000 Venezuelans who enter Cucuta (a Colombian city bordering Venezuela) daily, as many as 5,000 remain in the country.109 The majority cross the border for medicine or food, which are scarce in Venezuela.110 In 2018, there were approximately 1.1 million Venezuelans or Colombians who were previously living in Venezuela who migrated to Colombia. Of these, approximately 83% were in need of health and medical assistance when they arrived,111 suggesting that this may have been one of their major reasons for migrating. Unfortunately, this migration is causing diseases to spread more quickly among the migrants and into surrounding countries.112

The need for medication and treatment for HIV is one of the leading failures of the healthcare system that initiates migration out of Venezuela. In 2016, it was estimated that 39% of the 120,000 Venezuelans with HIV did not have access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), the treatment necessary to stop the progression of HIV.113 This low treatment rate poses a risk of increased transmission of the disease and a higher chance of developing AIDS—a progressed form of HIV that is often fatal.114 Since 2016, observers in Venezuela have reported that the situation continues to worsen as preventative measures, such as condoms, are not available to control the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.115 Venezuelans who are living with HIV can migrate to Brazil where they receive free ART and other care,116 or cross the border to Colombia where they can acquire proper HIV/AIDS treatment if they have health insurance.117,118 Treatment for HIV can be lengthy and require prolonged hospital stays, but many Venezuelans cross the border only temporarily to obtain treatment and medication that is unavailable through public healthcare in Venezuela.119

Mother and Infant Health

The health of mothers and infants are of utmost concern as the public healthcare crisis continues. Of pregnant women in Venezuela who are living with HIV, only 48% have access to the necessary medication and treatment to avoid perinatal transmission to their child.120 Even after a child is born, HIV can be transmitted while breastfeeding,121 indicating that access to medication for women is essential to protect future generations. Public healthcare decline also directly impacts the health of mothers who cannot obtain the necessary care to safely deliver their children. In Venezuela, 98% of children are born within a healthcare facility, but that statistic does not provide any insights into the conditions in which those children are born.122 Many women give birth to their children in hospital waiting rooms, as a bed is not available.123 Existing malnutrition, which affected 17% of Venezuelan children under five in 2018, combined with an inability to receive immunizations, increases children’s risk of contracting disease and later health complications.124 As a result of these and other healthcare conditions, maternal mortality increased by 65% between 2015 and 2016, and infant mortality increased by 30%.125

The severe inadequacy of mother and infant healthcare in Venezuela is evidenced by the number of pregnant Venezuelan women who cross the border into Colombia and Brazil in an attempt to safely deliver their babies. Within the first quarter of 2019, San José public hospital in Colombia reported assisting 1,000 Venezuelan women concerning pregnancy and birth—this is about 330 women per month.126 A single hospital reporting that they are assisting that many Venezuelan women with pregnancy-related concerns alone, depicts the scale of the impact the healthcare crisis has on mothers and their children. In Brazil, Venezuelan women who cross the border to deliver their babies are 20% more likely to need a Caesarean section (C-section) than Brazilian women.127 A C-section is generally performed to protect the life of a mother and child due to health conditions, such as the risk of passing an infection from mother to child;128 thus a higher C-section rate suggests higher rates of pregnancy and delivery complications. Furthermore, of the 43.6% of Venezuelan women who need C-sections, 63.2% are high risk pregnancies.129 In Venezuela, women cannot have regular check-ups throughout pregnancy due to low accessibility and high costs,130,131 often causing complications during birth. Studies have shown that insufficient prenatal care has a direct impact on infant mortality rates and leads to an increase in premature births and sudden infant death.132 Venezuela’s healthcare crisis is leaving mothers desperate as they try to safely deliver and provide for their children.

Expensive and Unconventional Means of Obtaining Medical Supplies

Because medical supplies are sparse in Venezuela, individuals are likely to turn to the black market to obtain supplies. Pharmacies are unable to purchase more medicine due to government restrictions, and hospitals are stocked through local pharmacies, so the healthcare they are able to provide is tied to the limited supplies available.133 An online black market has emerged to fill the need for supplies, and for many it is worth the risk.134 Drugs and equipment purchased through black market services are not guaranteed to be safe to use or the correct product for their healthcare needs, but often it is people’s only chance at survival. The medicines that are sold through the black market and street vendors are covertly brought from hospitals or neighboring countries.135 Vendors often do not properly store these medicines and they are sold even when expired.136 For many, these questionable medicines are their last attempt to survive due to a lack of available healthcare. A Venezuelan woman whose baby was in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) told reporters that she was required to provide her own catheters and needles for a surgery to save her child. She reports that they were only available to her on the black market, but there was no guarantee they were the correct supplies.137

Though medical supplies are more available on the black market than at healthcare facilities, Venezuelans often cannot afford the inflated costs. The people who purchase medicines through the black market or street vendors are often desperate, and because demand is high, the prices are more than most can pay. Pharmacies sell medications at 3% of the black market price, but—due to a government enforcement of the maximum price they can charge for medicine—pharmacies cannot afford to purchase more medicine as they make no profit.138 When doctors cannot provide the care necessary, or even relieve pain, individuals and families sell everything they can to purchase medicine on the black market. One Venezuelan explained that they sold everything, from their air conditioning unit to a cheese slicer, in order to purchase medicine “because life is more valuable than furniture.”139 Many of the diseases contracted in Venezuela are generally curable, but the cure is not available to most citizens. Family members will spend countless hours in the streets and online waiting for hope, even if it comes in a discolored bottle.140

Practices

Venezuela has struggled with healthcare issues for decades, and the government has sought to implement policies to overcome the crisis. Venezuela’s universal healthcare and socialist government means that it is expected the government will be heavily involved in providing healthcare to all of its citizens, thus the Venezuelan government implemented the Barrio Adentro program in 2003. As previously mentioned, this program had considerable success, yet over time contributed to the healthcare crisis in Venezuela. Concerted effort and investment in Barrio Adentro is the only practice in Venezuela specifically targeted at changing public healthcare. In a country where healthcare is public and controlled by the government, government intervention is the only way to directly solve a healthcare crisis. The following are other practices that are seeking to overcome the factors contributing to the healthcare crisis and the devastating impact it is having in Venezuela.

Increasing Local Supplies Accessibility

Organizations within Venezuela are providing options other than the black market or street vendors to those struggling to obtain safe medication. Medical supplies are gathered from foreign hospitals and donations from partner organizations and then distributed to individuals who need these resources. The medicine, treatments, and supplies are essential in providing healthcare to the people in Venezuela and overcoming the lack of availability and inflated costs.

Acción Solidaria is a nonprofit organization started by and run by Venezuelan Feliciano Reyna. The medical aid group seeks to bring foreign aid into Venezuela and distribute it to doctors and patients in need.141 The organization began with a focus on those suffering from HIV and the severe lack of treatment available to them, but has expanded to the point that medication of all kinds can be picked up for free with verification of a prescription.142 Reyna works closely with organizations around the world to collect and search for supplies and medicines for Venezuelans with chronic diseases, who do not have the ability or means to obtain regular treatment and medication options otherwise.143 Additionally, the medical supplies come through donations that are often from individuals who have completed treatment or changed medication.144

Impact

Though Venezuelan authorities make it difficult to bring donations into the country and properly distribute them, Acción Solidaria has had much success. Donations come from 17 countries around the world. Between 2016 and 2017, there were 12,226 direct donations to Acción Solidaria and 10,667 sent through partner organizations.145 It is difficult to determine the impact the organization is having overall, though anecdotal evidence is available to provide some additional insight into their success. Elizabeth Rivas, one of the many Venezuelans suffering from hypertension, reports receiving her prescription for free from Acción Solidaria to keep her life-threatening disease under control.146 Her search for medicine started with a call to one of Acción Solidaria’s call centers where they have received 1,500 requests for medication each month, which they seek to fill with donations.147

Gaps

There is a major gap in the analysis of the effectiveness of this organization as there are no numbers available to detail how many phone calls requesting medication have been fulfilled or the overall impact they are having on the healthcare crisis at this time. The WHO recommends providing donations of untouched medical supplies that are not from individuals because of high risk, yet many donations are received from individuals rather than from institutions.148

International Organization Involvement in Venezuela

Navigating how to aid Venezuela can be difficult for international organizations because they cannot send money, as it will go straight into the hands of the government. To combat this challenge they are primarily sending supplies and vaccinations to improve Venezuelan healthcare by assisting medical workers and providing essentials to more Venezuelans.

One leading organization involved in the international response is the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). In conjunction with its many partners, USAID seeks to administer vaccinations in countries that border Venezuela, putting together response teams, clinics, and technical support. Their main focus is on preventing, detecting and treating infectious diseases that plague Venezuelans. They provide specific staff training to help with the needs of Venezuela and their healthcare system and provide additional staff and equipment to local clinics. USAID stockpiles medicine in the border countries of Colombia and Peru to assist with Venezuelan migrants and to be ready for when the government is willing to let aid in that could assist tens of thousands.149

Impact

Outbreaks in Venezuela of measles, rubella, and diphtheria drew international attention, bringing an increase of vaccinations to the country. From April 2018 to February 2019 over 8.3 million young children were vaccinated by USAID and PAHO.150 In the first few months of 2019, hygiene supplies were provided to help 35,000 Venezuelans maintain health and avoid contracting disease. Additionally, medical supplies and pharmaceuticals were sent in emergency kits to aid 40,000 people for up to 90 days.151 Although this data suggests that international organizations have been able to help many Venezuelans, it only illustrates the outputs of international aid given and not the true impact.

Gaps

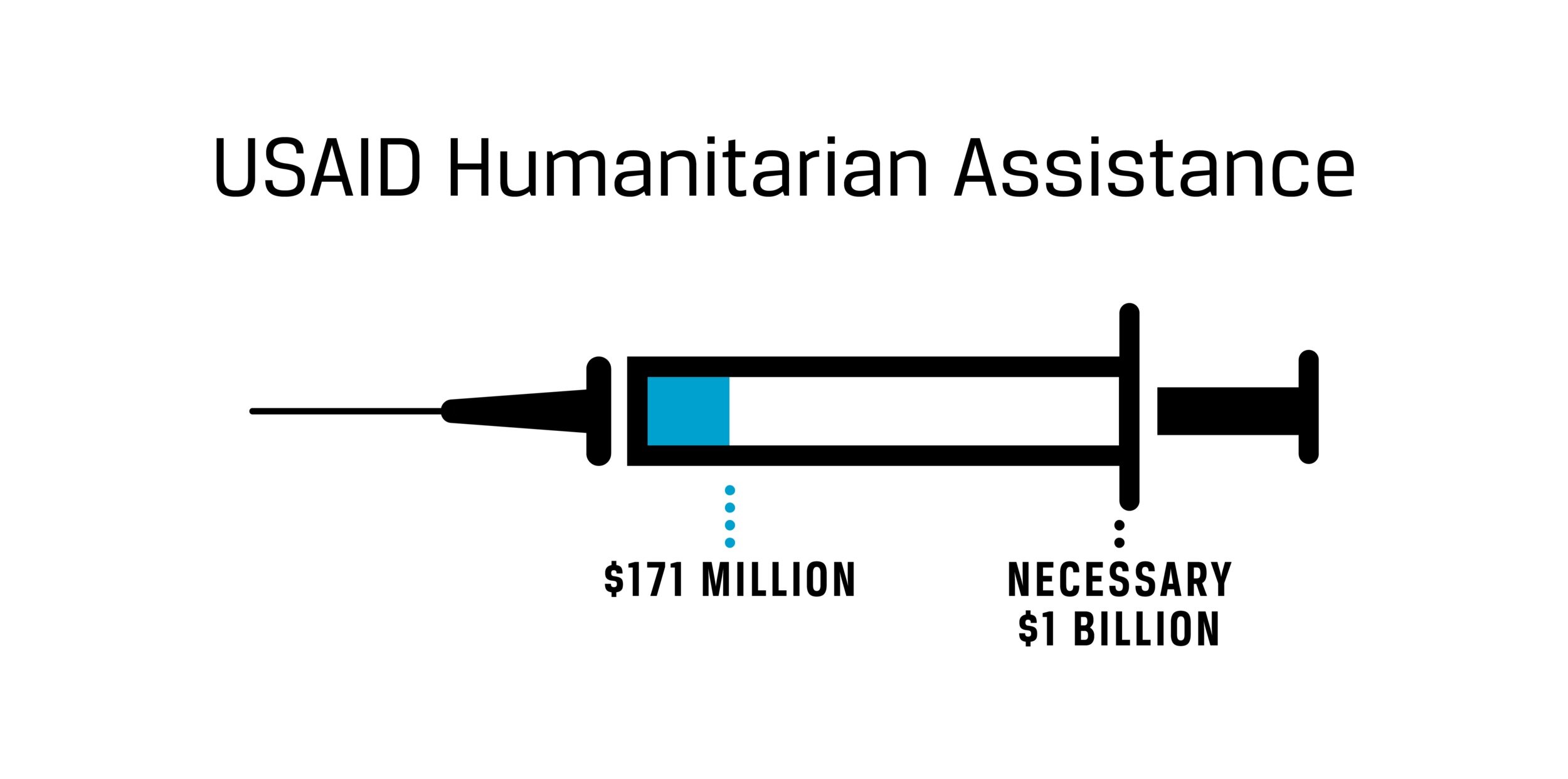

International assistance has been proven to improve healthcare in developing countries. A Stanford study of 140 countries around the world estimated that an increase in health aid to $1 billion could lead to fewer deaths in children under 5 (a good indicator of improved healthcare).152 USAID reported that since 2019, they have provided $171 million in humanitarian and development assistance to Venezuela, but a major gap still remains in order to reach the $1 billion that will allow for real change and impact. Further, the $171 million that has been provided in international aid is not solely focused on healthcare assistance.153 The UN has estimated that one fourth of Venezuelans are in need of humanitarian assistance,154 but the aid being provided is likely not reaching the impact intended and desperately needed. According to the WHO, only approximately 10–30% of medical device donations made to low-income countries are used and operated regularly.155 The other 70–90% lay in the streets, never used due to lack of electricity or understanding of the technology.156 Further, the millions of Venezuelan children that are vaccinated with the supplies that USAID provides still fails to reach the essential immunization level of 90–95%, and thus outbreaks will continue to occur.

Border Healthcare

Due to government restrictions and lack of action in regards to healthcare in recent years, neighboring countries and organizations provide healthcare along the border to make up for the lack of healthcare in Venezuela. Venezuelan migrants, temporary and permanent, are receiving lifesaving healthcare that is unavailable in Venezuela.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), also known as Doctors Without Borders, is especially prevalent in the Colombian regions of La Guajira, Norte de Santander, and Arauca.157 Though MSF was present in parts of Venezuela beginning in 2015, the organization has left some areas of Venezuela due to difficulties negotiating with the government. In 2018, they started assisting Venezuelans from a center in Boa Vista, Brazil—where many people leaving Venezuela go to seek healthcare.158 MSF focuses on providing day-to-day and long-term care to overcome endemic and chronic diseases.159 The focus is primarily on mother and infant health because of the risks of giving birth in Venezuela.160 There are also many Venezuelans who cross the border to receive help in family planning from MSF before returning to Venezuela.161 Venezuelans cannot receive public healthcare in Colombia, as stated in the law, except for in emergency situations. Because of this, only about 1% of Venezuelans who reside in Colombia have access to healthcare.162 Thus, MSF seeks to provide aid for the 99% of Venezuelans in Colombia who are still in need of healthcare assistance.

Regions where Doctors Without Borders is most active

Impact

In 2018, MSF built three healthcare facilities in Colombian departments to provide primary and mental care for Venezuelans, as they did not have access to public healthcare. Within a six month period from 2018–2019, 12,000 Venezuelans received health care from MSF.163 By the end of 2019, those consultations rose to over 50,000, promising continued care moving forward.164 It is reported that many women travel across the border to specifically receive hormonal implant contraceptives, as they are aware they do not have the adequate health to deliver and care for a child.165

Gaps

There are over 350,000 Venezuelans in the Colombian regions where MSF is centered, yet only 50,000 have received some form of healthcare.166 Though the focus is on assisting migrants, it is improving the lives of many Venezuelans who have the option to then return to Venezuela healthier. As the practice is more recent, there is limited data to show the impact it is having specifically within Venezuela.

Preferred Citation: Bittleston, Valerie. “Public Healthcare Crisis in Venezuela.” Ballard Brief. July 2020. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints